Punctuated Equilibrium and Patterns from the Fossil Recordlast updated 9/18/04by Casey Luskin Introduction: Evolution postulates that new species are descended from other pre-existing species, and that populations of the pre-existing species changed into the new species over periods of time. Evolution thus predicts that there were organisms that existed at transitional stages while one form turned into another. It is possible that evidence of these evolutionary transformations may be found in the fossil record. This was noted in Origin of Species, by the famous British naturalist Charles Darwin: Two types of Evolution The term "evolution" simply means "change through time," there are two types of evolution: macroevolution and microevolution. Microevolution is "slight, short-term evolutionary changes within species."2 For example, within humans, there are different eye colors, hair colors, and skin colors. These are the result of microevolution. In contrast, macroevolution is "the origin and diversification of higher taxa"2 or, "evolutionary change on a grand scale, encompassing [among other things] the origin of novel designs…"3 There is thus a fundamental difference between microevolution and macroevolution. Understanding Evidence: When scientists propose hypotheses, they first make observations of the evidence. Sometimes they then make inferences based upon the evidence to create a hypothesis about what happened. When it comes to the fossil record, out of thousands of species known, only a few are claimed to be Darwin's intermediate forms. Fossil evidence of intermediates are generally absent, as paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould explains:  Appealing to Incompleteness: Darwin saved his gradual theory of evolution by claiming that intermediate fossils are not found because "[t]he geological record is extremely imperfect"1 and thus it just so happened that the intermediate links were not the ones fossilized. Gould noted in 1977 that Darwin's argument that the fossil record is imperfect "still persists as the favored escape of most paleontologists from the embarrassment of a record that seems to show so little of evolution directly."21 Paleontologists emphasized that the "jumps" between species without transitional forms, were not simply the result of an incomplete record: Quote Mining and Cherry Picking? Some might claim that citing these authorities over the lack of transitional forms misrepresents their views or constitutes "mining" their writings for quotes that fit this argument, while excluding portions that don't fit. Stephen Jay Gould complains creationists misuse his quotes about the lack of transitions: "[t]his quotation, although accurate as a partial citation, is dishonest in leaving out the following explanatory material showing my true purpose--to discuss rates of evolutionary change, not to deny the fact of evolution."13 It should thus be acknowledged that each author cited thus far is an unswerving evolutionist. Ernst Mayr, proclaims his belief that "[e]volution is no longer a theory, it is simply a fact."12 But these convictions do not invalidate the fact that the fossil record generally lacks plausible candidates for transitional forms. As explained next, many evolutionists have tried to accommodate the lack of transitions into evolutionary theory by claiming the lack of transitionals tells more about the rate at which evolution occurred rather than whether or not evolution happened. Punctuated Equilibrium Because the fossil record did not exhibit Darwin's predicted slow and gradual evolution with transitional forms, some paleontologists sought to find a theory of evolution where, "changes in populations might occur too rapidly to leave many transitional fossils"13 (see Figure 2--modeled after figure 8 from Gould and Eldredge 1977 (see ref 17).  In 1972, Gould and Eldredge proposed the theory of "punctuated equilibrium" where most evolution takes place in small populations over relatively rapid geological time periods. By reducing the numerical size of the transitional population and the number of years for which it exists, punctuated equilibrium greatly limits the number of organisms bearing transitional characteristics. Since many organisms are not fossilized, this increases the likelihood that transitional forms would not be fossilized. One strength of this theory is that Gould and Eldredge claim it is predicted by population genetics. But what are the implications of punctuated equilibrium? Under punctuated equilibrium, species usually change little as, "gradual change is not the normal state of a species."4 Large populations may experience, "minor adaptive modifications of fluctuating effect through time" but will "rarely transform in toto to something fundamentally new."4 This is called "stasis." But small "peripheral" populations may allow for more change at a quicker rate. Gould argued that most macroevolutionary change takes place in such populations during "speciation" such that there is insufficient time for the transitional forms to be fossilized: Ernst Mayr wrote, "[a] primary tool used in all scientific activity is testing."13 Theories are testable when they make predictions which scientists can in principle observe. Though philosophers of science do not universally agree upon a definition of science,14 many have stated that scientific theories must be based upon repeatable observations,15 subject to testing,13, 16 and "falsifiable," as observations could disconfirm the theory.13 But what hard evidence does punctuated equilibrium predict? With respect to finding fossil evidence of the transitional stages of evolutionary change, punctuated equilibrium predicts that direct fossil evidence of these transitional morphologies will tend to not be found. The theory of punctuated equilibrium may still predict certain patterns which may be found in the fossil record, but as Steven Stanley explains, the theory is untestable against special creation and leaves scant trace of Darwin's mechanism at work: Punctuated Equilibrium and Genetics Gould and Eldredge justify their model of rapid speciation by claiming that it is predicted by population genetics. According to "allopatric speciation" biological change is most likely to occur in small populations which are "reproductively isolated" or separated from the main gene pool of a population. In these cases, there is a stoppage of gene flow from one population to the other, and thus variation in the smaller population can persist, and undergo further change without being "drowned out" by the gene pool of the larger population. Essentially, there has been a recognition that speciation, which purports to explain the rapid and large morphological jumps in the fossil record, may require too much biological change in too little time. Gould and Eldredge write that criticisms of punctuated equilibrium come from evolutionary biologists who have recognized that it requires large rapid genetic changes: Gould and Eldredge counter that variation could exist in the larger population before reproductive isolation was achieved and speciation could take place:

Based upon the fossil record, and following the traditional mode of explanation under punctuated equilibrium, the variation must originate during a speciation event. But how fast did Gould and Eldredge claim speciation occurred? "Geographic isolation leading to reproductive isolation need not take long to occur: our estimate was from five thousand to fifty thousand years.20 (Eldredge) "I'd be happy to see speciation taking place over, say, 50,000 years…21 (Gould) 10-9 mutation / loci / year x 50,000 years = 0.00005 mutation / loci This implies that in 50,000 years, a species can undergo at the very maximum a 0.005% total change in its DNA through the traditional point mutation mechanism of genetic change during a speciation. Given that genetic variation within a species can range much higher than 1%, this very small amount of genetic change possible during a speciation event seems insufficient to justify the many rapid and large transitionless morphological jumps in the fossil record which punctuated equilibrium purports are possible during speciation. Though some evolutionary biologists believed the rapid appearance of species could be accounted for by neo-Darwinian population genetics, they were critical of punctuated equilibrium: According to paleontologists, almost all of the major living animal phyla appear in the fossil record during the Cambrian Period, about 550 million years ago (see Figure 4). This takes place within a 5-10 million year period which has been called the "Cambrian Explosion." It is unlikely that any theory of evolution can account for the lack of transitional forms, because it must generate simply too much biological complexity too quickly:

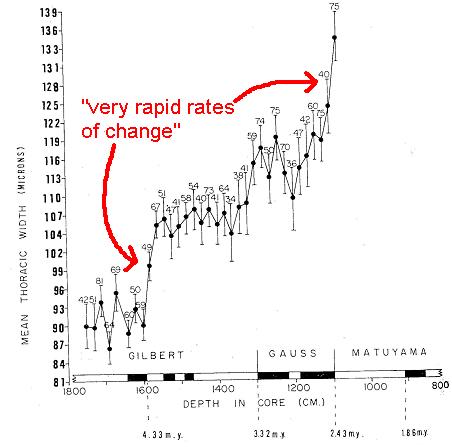

The Cambrian Explosion is by no means the only "explosion" in the fossil record. One evolutionist concedes that for the origin of fishes, "this is one count in the creationists' charge that can only evoke in unison from paleontologists a plea of nolo contendere [no contest]."31 Plant biologists have called the origin of plants an "explosion," saying, "[t]he … radiation of land [plant] biotas is the terrestrial equivalent of the much-debated Cambrian 'explosion' of marine faunas."32 Vertebrate paleontologists believe there was a mammal explosion because of the few transitional forms between major mammal groups: Conclusion: Out of thousands of species in the fossil record, only a few are claimed to be transitional forms. This lack of transitional forms poses, as Darwin said, "the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against [evolutionary] theory."1 And, at least to this point, it appears to be an objection that is unsolved by evolutionists. References: 1. Darwin, C., The Origin of Species (1859).2. Futuyma, D., Evolutionary Biology, pg. 447, glossary (1998). 3. Campbell, N. A., Reece, J. B., Mitchell, L. G., Biology 4th Ed, pg. G-13 (1999). 4. Gould, S. J., "Is a new and general theory of evolution emerging?" Paleobiology, vol 6(1), p. 119-130 (1980). 5. Gould, S. J., "Evolution's erratic pace," Natural History, Vol. 86, No. 5, pp.12-16, (May 1977, emphasis added). 6. Eldredge, N. and Tattersall, I., The Myths of Human Evolution, pg. 59 (1982). 7. Benton, M. J., Wills M. A., and Hitchin, R., "Quality of the fossil record through time," Nature Vol 403:534-536 (February 3, 2000). 8. David S. Woodruff, Science, pg.717 (May 16, 1980). 9. Eldredge, N., Reinventing Darwin, p. 95 (1995). 10. Carroll, R., Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, pgs. 8-10 (1997). 11. Pagel M., "Happy accidents?," Nature, Vol 397, pg. 665 (February 25, 1999). 12. Mayr, E., What is Evolution, pg. 189 (2001). 13. See Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science (National Academy Press, 1998), pg. 43, 56, 57. 14. Essays by Larry Lauden in But Is It Science? Edited by Michael Ruse. (Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1988). 15. Science and Creationism, A View from the National Academy of Sciences, 2nd Ed (1999). 16. K. Popper, Conjectures and Refutations, p. 257 (1963). 17. Stanley, S., Macroevolution, pg. 93. It should be noted that in Gould and Eldredge's 1977 paper, "Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered," (Paleobiology 3:115-151), they do give specific data in favor of punctuated equilibrium. They state that "the model of punctuated equilibria is eminently testable..." (p. 120). Gould and Eldredge state find that the case of the radiolarian Pseudocobus vema provides good documentation of two very rapid periods of change. This species was put forth by a critic of punc eq which makes it significant that Gould and Eldredge can claim that it supports their theory. The diagram documenting this change through time is pictured below (his figure 3):

My comments are in red. Very rapid rates of change is a pattern, not an explanation or a process. But what is the mechanism of these "very rapid rates of change?" Why must it be Darwin's theory of mutation - and selection when this is perhaps equally consistent with the rapid infusion of information into the biosphere by an intelligent agent. If an intelligent agent were to infuse large amounts of information into the biosphere, is this not exactly the sort of pattern we might expect to find? Additionally, Gould and Eldredge find other cases in favor of the "punc-eq" pattern, the radiolarian Eucyrtidium calvertense, the history of the trilobite Placoparia, and even cited that punc eq has been used to explain the origin of Homo sapiens. Devonian brachiopods are also cited as evidenc of punc eq, where one commentator wrote, "In twenty yeasr work on the Mesozoic Brachiopods, I have found plenty of relationships, but few if any evolving lineages ... What it seems to mean is that evolution did not noramlly proceed by a process of gradual change of one species into another over long periods of time..." Though many have tried to give mechanisms, punc eq could be seen more fundamentally as simply a pattern in the fossil record with rapid morphological change followed by periods of stasis. But a pattern is not a process--what is the process which can account for this pattern? Is this pattern more consistent with the process of intelligent design, or Darwinian evolution. On its face, intelligent design is capable of infusing large amounts of information into the biosphere rapidly, which could result in this rapid morphological change. In contrast, on its face, Darwinian evolution requires forms go through intermediate stages. Thus, Gould has appealed to developmental mutations (see ref. 4) to account for rapid changes and hold faithful to neo-Darwinian mechanisms of change. But at what point does this become special pleading where we must always invoke special developmental mutations to create rapid morphological change which is somehow both functional and advantageous? On its face, neo-Darwinism would not predict a pattern of punc eq in the fossil record, implying that punc eq is a poor vehicle for testing if stepwise mutations occurred. 18. Gould, S. J., Eldredge, N., "Punctuated equilibrium comes of age," Nature Vol 366:223-227 (November 18, 1993). 19. See "Punctuated Equilibria: An Alternative to Phyletic Gradualism" Eldredge and Gould in T.J.M. Schopf, ed., Models in Paleobiology. 1972, pg. 106. 20. Eldredge, N. The Triumph of Evolution and the Failure of Creationism (2000). 21. Stephen Jay Gould as quoted in Lewin, R., "Evolutionary Theory Under Fire," Science Vol 210:883-887 (November, 1980). 22. Charlesworth, B., Lande, R., and Slatkin, M., "A Neo-Darwinian Commentary on Macroevolution," Evolution, 36(3) 1982 pg. 474-498. 23. Denton, M., Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, pg. 193 (1986). 24. Ohno, S., "The notion of the Cambrian pananimalia genome," Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol 93 pg. 8475-8478 (August 1996). 25. Barnes, R.S.K., P. Calow, P.J.W. Olive, D.W. Golding, J.I. Spicer. The Invertebrates: A New Synthesis 3rd Ed. (2001). 26. "Catching the first fish" by Philippe Janvier; Nature 402:21 - 22 (1999). 27. Dawkins, R., The Blind Watchmaker, pg. 229-230 (1986). 28. James W. Valentine, Stanley W. Awramik, Philip W. Signor & Peter M. Sadler, Evolutionary Biology (1991). 29. Gould, S. J., "On Embryos and Ancestors," Natural History, July/Aug 1998, pg. 64. 30. See Meyer, Nelson, Chien, and Ross in "The Cambrian Explosion: Biology's Big Bang," in Darwinism, Design, and Public Education, edited by J. A. Campbell and S. C. Meyer, pg. 326 (reference 6) (2003). 31. Arthur Strahler's anticreationist book, Science and Earth History – The Evolution/Creation Controversy Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1987. 32. "Early Evolution of Land Plants: Phylogeny, Physiology, and Ecology of the Primary Terrestrial Radiation" Annual Review Ecol. Syst. 1998, 29:263-292. 33. Eldredge, N., The Monkey Business: A Scientist Looks at Creationism, pg. 65-66, (1982). 34. Cooper, A., and Fortey, R. "Evolutionary Explosions and the Phylogenetic Fuse" Tree vol 13, no 4 (1998). 35. Hawks, J., Hunley, K., Sang-Hee, L., Wolpoff, M., "Population Bottlenecks and Pleistocene Evolution," J. of Mol. Biol. and Evolution, 17(1):2-22 (2000). 36. "New study suggests big bang theory of human evolution" (January 10, 2000), at http:// www.umich.edu/~newsinfo/ Releases/2000/Jan00/r011000b.html" (accessed 10/21/03). 37. Darwin, Charles, The Origin of Species available online at http://www.literature.org/authors/darwin-charles/the-origin-of-species/chapter-06.html (accessed October 6, 2004) |